Once our group arrived together at the accommodation in London, we were guided through the underground metro stations by our London guide, David, where we eventually came back to surface level at the Hyde Park Corner stop on the Underground. This was our first encounter and discussions on the British perspectives of memory during both the First World War and the Second World War. Several significant memorials were located here, but we started at the Royal Artillery WWI and WWII Memorial. This memorial was quite controversial at the time of its construction due to its representation of a dead soldier––this heavily contrasted the former customs of relying on Roman or Greek symbols that may have glorified war by showing the mortality of man (specifically a British man) and the true psychological toll that the collective British population felt during the First World War. Adjacent to the Artillery Memorial is the Australian WWI and WWII Memorial, a concave wall engraved with the every city that an Australian soldier was born, with some of these engravings agglomerating to reveal the major battlefields where many had died. Across the park from this is the New Zealand WWII Memorial, which appears like a field of crosses as you glance at it on your approach. [deals with cultural relations between NZ and GB]. We then made our way into Hyde Park to the Canadian WWII Memorial.

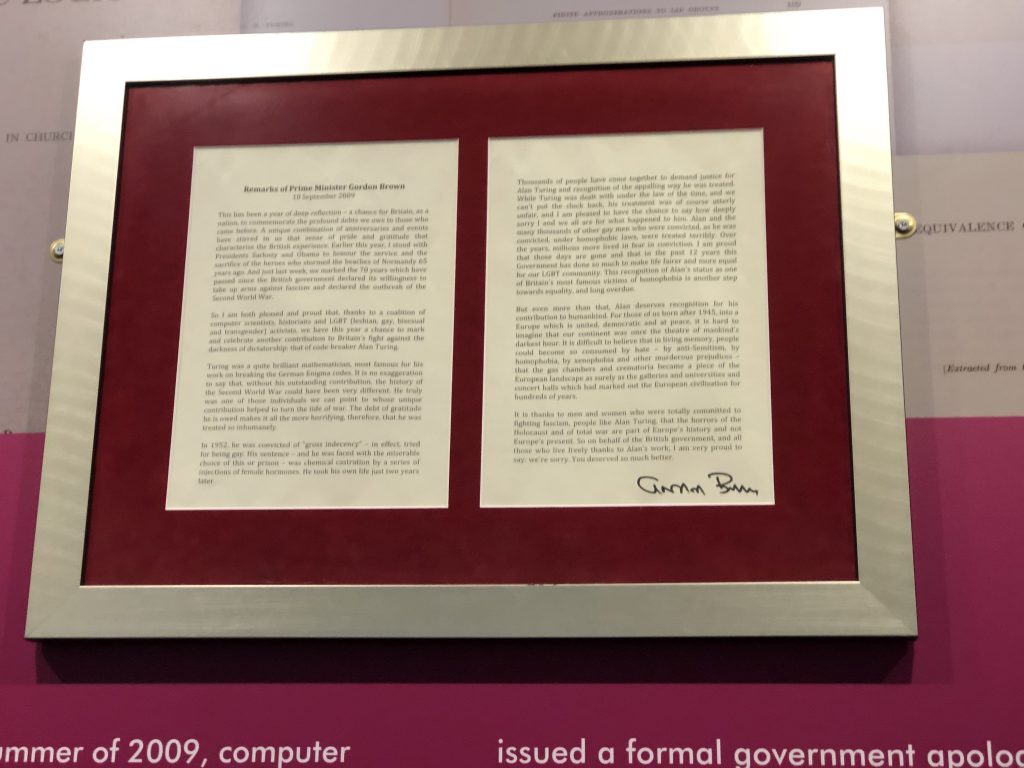

The next day we traveled out to the countryside to Bletchley Park, the location of GB’s secretive codebreaking operation. This complex held thousands of workers and some of the world’s most brilliant mathematicians in order to break the code machines of the Axis Powers. Though much of the action occurred indoors and under cramped conditions, the complex did include a significant portion of outdoor, somewhat pastoral, green space to relieve some of the stress of the working conditions. The museum also has collections of the various Enigma machines as well as the Lorenz machines that were used during WWII. In addition it has a special exhibit to Alan Turing, one of the leading heads and exceptional mathematician, who was eventually jailed after the war due to his sexual orientation. However, Britain (though five decades after Turing’s suicide), issued an apology of their mistreatment of him by imprisoning him due to discriminatory laws. To me, this step was a reckoning of the contributions that Turing made to the war effort, and an understanding that his legacy was far more important that the laws that eventually led to his death––laws that Britain perhaps would like to forget about.

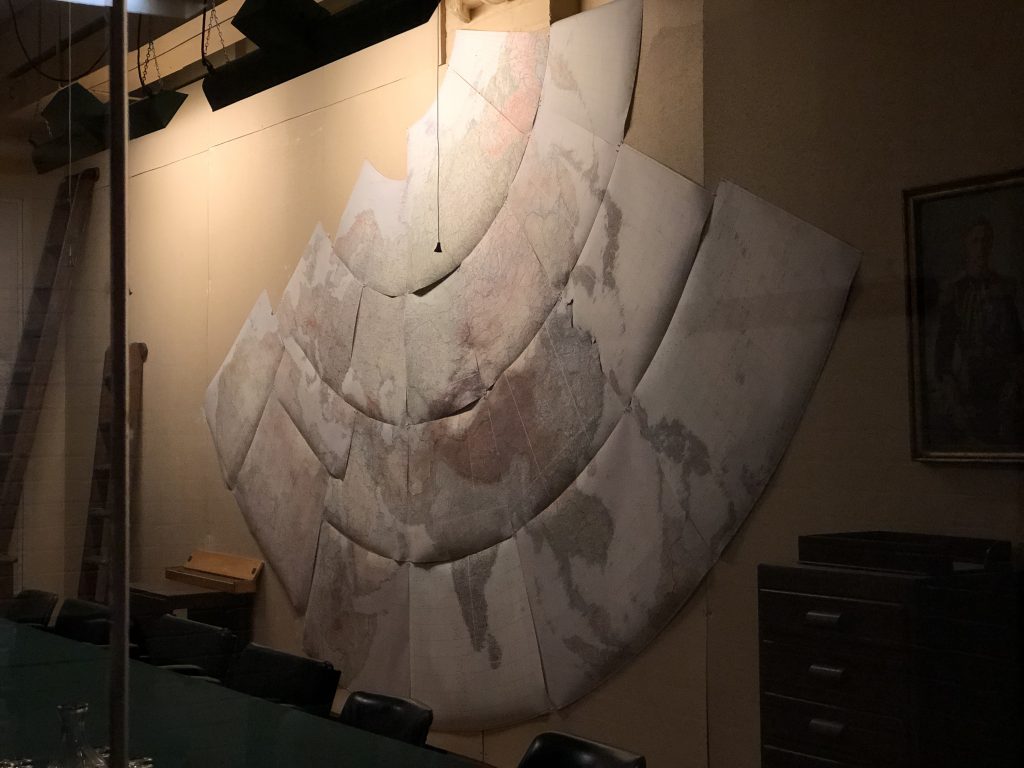

Our final morning in London we began at the Imperial War Museum (our tour guide nodded to the controversy of the name of this museum in the British society), where we were able to see some of the many machines that played a role in the victory to Britain (and its allies) and their ability to shift narratives in power during WWI and WWII. At the conclusion of the tour here, we took a jaunt to the Cabinet War Room Museum, which showed the working conditions of Churchill’s War Room Bunker. This museum certainly played up Churchill’s persona and influence during WWII.