How can one treat vital memory like it’s an amusement park, as if tragedy has become only a pop-culture icon within a city’s tourism opportunities? When “empathy” has become fashionable, that’s exactly what is at stake––as present at the Anne Frank Huis in Amsterdam.

An amusement park is what it felt like inside the museum and house: you must wait until there was adequate space in the museum for you to wander to enter the rooms; when in the rooms, you had to wait in line to go to the next space; the walls and finishes of the interiors were all replaced, like kitschy and fake wallpapers that you might see at a Disney ride; and though there were diagrams to explain your placement within the house, you never had a feeling for where in the house you actually were (this kind of place could be put anywhere in the world, and it would have felt exactly the same). But where I believe the museum got the place of memory the furthest from Otto’s intentions was in its false sense of emptiness. When the house was to be converted into a museum, Otto Frank asserted that he believed the house should be empty, such as how it looked after the Nazis raided the house and evicted the Frank family (minus, of course, the bookshelf that hid the secret Annex where they had hid). To wander completely alone, in total emptiness, to dwell on not only the memories of removal of the families that lived there, but also memory of the life that had occurred there, would be inexplicably powerful. Unfortunately, the house (as empty as it appeared) was full: full of people, full of waiting, full of sadness, and full of displays to protect the still living artifacts showing the life of the Frank family.

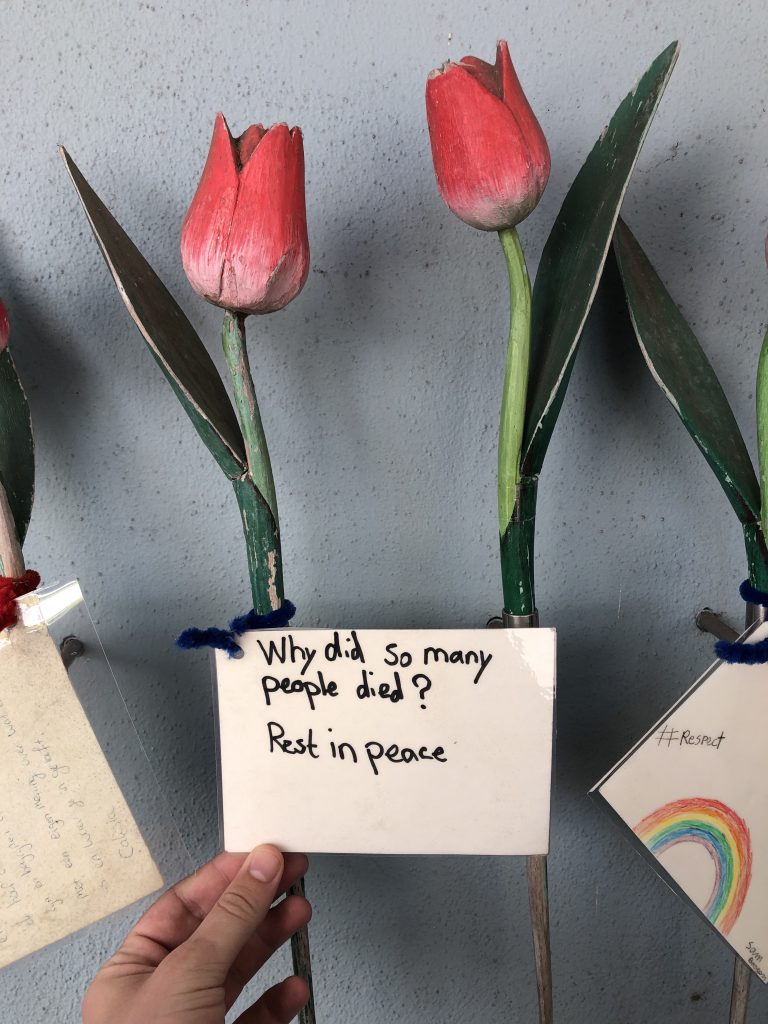

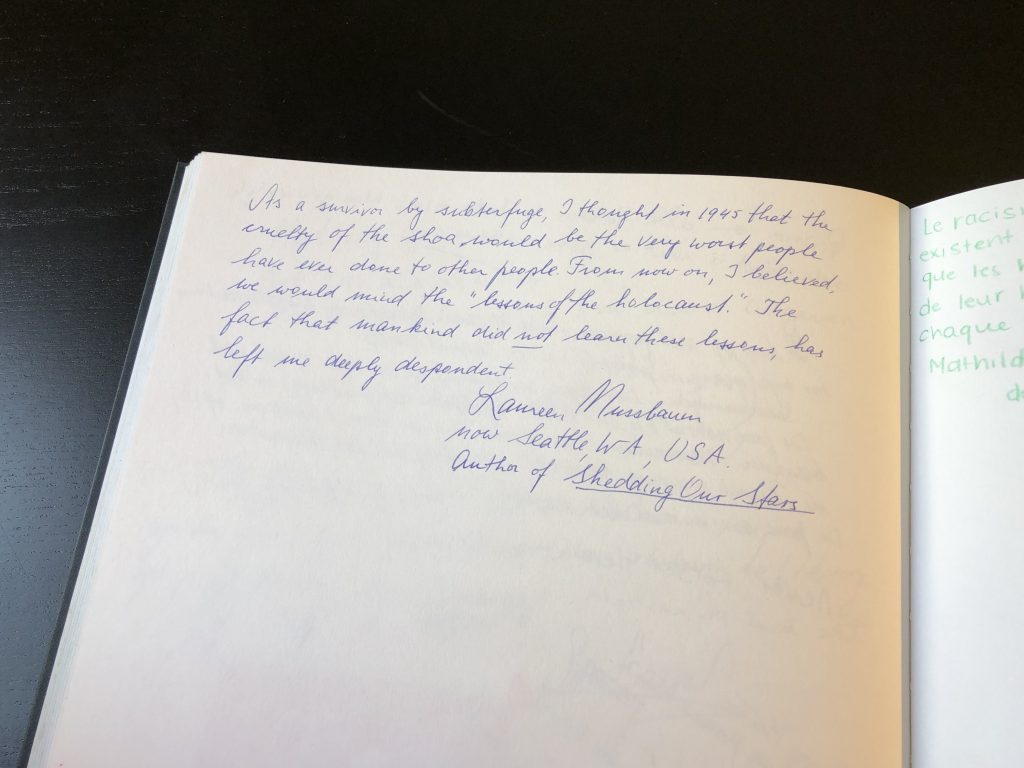

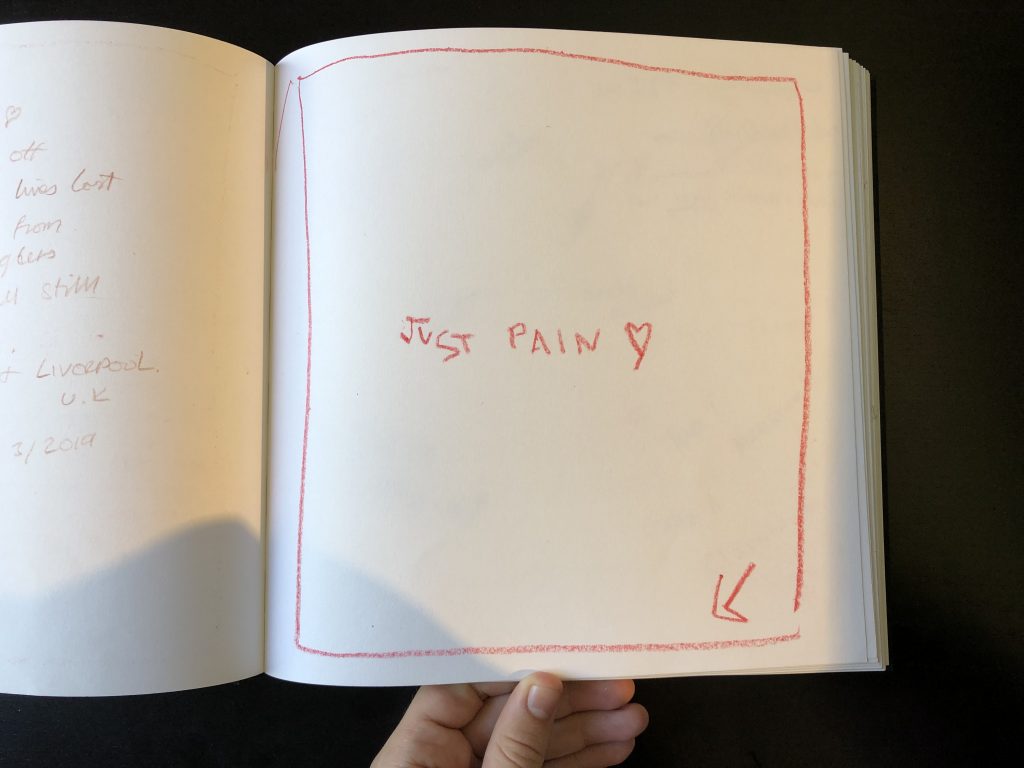

My feelings towards these types of situations are quite strong, but there was another place in Amsterdam that had a redemptive quality on the etiquette of memory and how this should be portrayed. At the Hollandsche Schouwburg (a museum located within the walls of the theater that was used to hold Amsterdam’s Jews before deportation), the exhibitions were interactive. While they showed important information on the Holocaust and its effects, there were some exhibitions that were intended to be interactive which required critical thinking on the Holocaust and its portrayal. There were a few spots in the museum where visitors could leave their feedback on the museum (claimed to help improve the museum, though I think these spots help other visitors to reflect on what they’ve seen), which began a dialogue not only on the exhibition, but also on how to actually exhibit the information in a way that inspires visitors to act so that the horrible acts which occurred in the Holocaust will not be replicated again in the future.