Photos and essay by Rachel Rines.

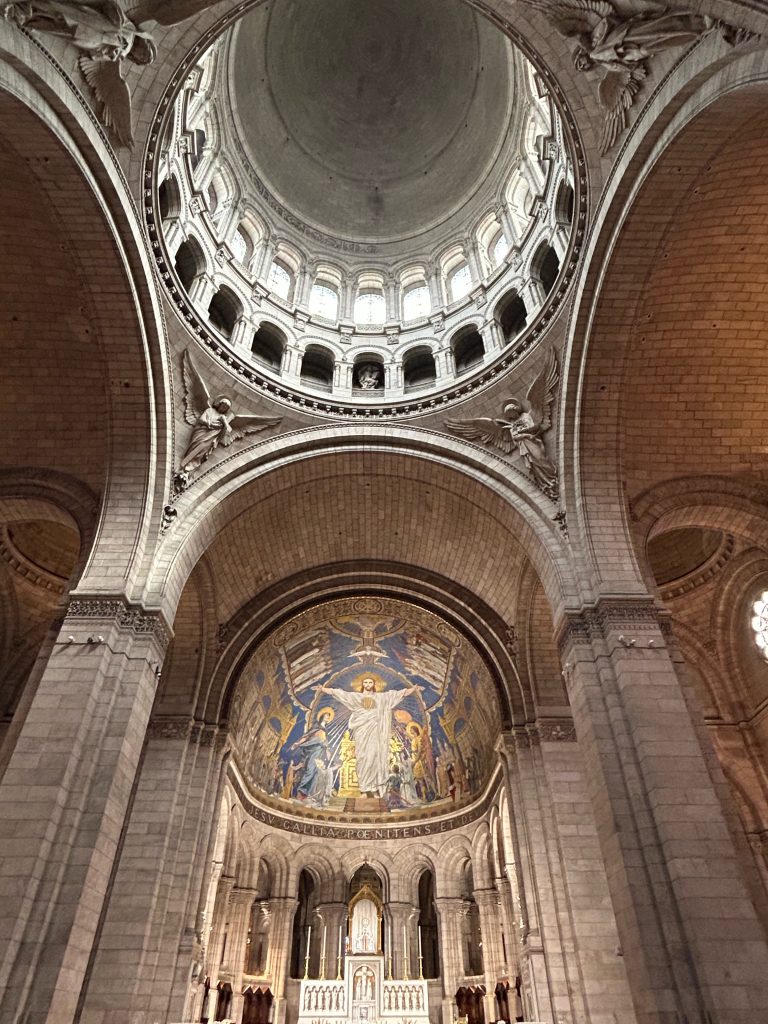

In Pierre Nora’s anthology of French national history, Realms of Memory, author André Vauchez finds that the cathedral is a stratified, or layered, place of memory. Individually, they are “memorial sites of French history, both sacred and profane.”

In researching the function of cathedrals in French society throughout history and now, I identified four layers of memory.

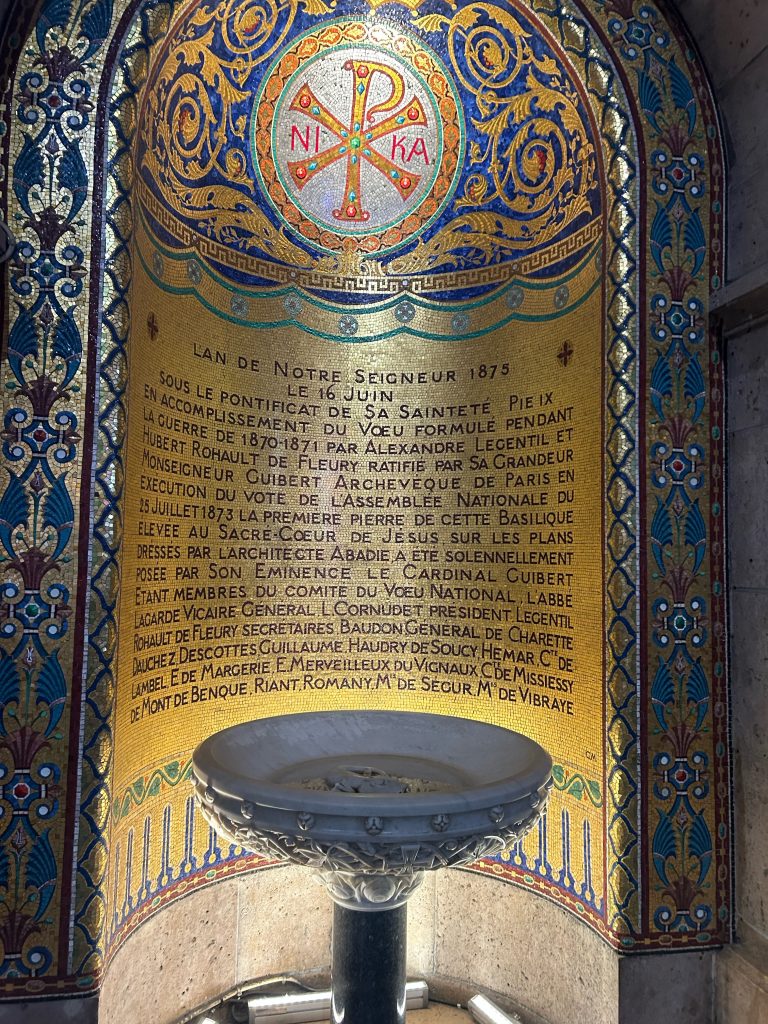

The first is replacement memory, employing the idea that sites of memory can be replacing old significance and meaning with new, such as the Cathedral of Chartres’ construction upon a former cult site as well as the mosque in Córdoba’s conversion into a cathedral after the Spanish Reconquista. More famously, the Notre Dame is built upon the ruins of two churches, as well as what is thought to be the site of a martyrdom.

The second is Christian historical memory, which essentially “turns the past into an internal present” (Vauchez). Cathedrals illustrate the Christian perception of time, which is not linear, but preparation for the coming of Christ, continuing the teachings of the Apostles. They incorporate depictions of the footsteps of Jesus, Mary, and the Saints, further implying the ever-presence of Christian belief.

The third is urban historical memory, as cathedrals evoke the memory of the city and/or diocese itself. During the French Revolution, many parts of cathedrals were destroyed or secularized. They were restored after the Revolution, but, for many, they were still associated with the Ancien Regime, and therefore the history of France as a nation.

The final layer of memory is ideological memory. The publishing of Notre-Dame de Paris in 1831 allowed people who were hostile or indifferent towards Christianity to find a place for themselves. With the increase in the openness of the Church throughout the 20th century, most notably with the Second Vatican Council, the accessibility of the Church became widespread. The Novus Ordo was established, allowing the Mass to be celebrated in the vernacular. Pope St. John XXIII (1958-1963) stated, “I want to open the windows of the Church so that we can see out and the people can see in.”

Additionally, cathedrals combine Christianity and nationalism. Because the construction of these cathedrals was collaborative between the religious and the monarchy, they evoke French pride and nationalism – the “genius of France.”